Report

States Lead the Way

04. 13. 2022

Reimagining the Social Safety Net Through Implementation of a Guaranteed Income

Why should states engage with guaranteed income?

Every person deserves to live with dignity and have their basic needs met. After decades of rollbacks and disinvestment, our current social safety net is insufficient given the economic situation we face. In the United States there is unconscionable and accelerating wealth inequality,1 wages have been stagnant for 40 years2 and, both before3 and throughout4 the coronavirus pandemic, many Americans struggle to meet their basic needs. In the richest country on Earth, elimination of deep poverty is attainable and long overdue. Historically, states have played a critical role in testing concepts to improve the lives of low-income residents and created a blueprint for anti-poverty measures that can be implemented nationwide.5 It is time to boldly reimagine and revitalize an eroded social safety net, and states have an opportunity to lead by example.

It is time to boldly reimagine and revitalize an eroded social safety net.

The devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted mitigation strategies intended to get cash to people who were impacted. Federal policies such as increased unemployment insurance, an expanded and fully refundable Child Tax Credit (CTC), and stimulus checks have led to burgeoning support for permanent cash transfer programs like a guaranteed income. Additionally, state and local governments added to relief efforts by using federal dollars provided by both the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to fund cash transfer programs of their own.6

At the same time, an increasing number of municipalities and other units of local government across the country are exploring guaranteed income demonstrations in their community, and states should seize this opportunity to build upon this work. Local guaranteed income programs, though limited in scope, produce incredibly valuable data to prove the efficacy of unconditional cash programs, which are critical for states to obtain buy-in from the necessary stakeholders. One limitation of local programs, however, is that they often aren’t scaled to study the potential for community-level change or other broader economic impacts.

At the federal level, the expanded CTC being debated as part of President Biden’s American Families Plan represents a form of guaranteed income for 39 million households.7 Unfortunately, federal conversations around nationwide cash transfer programs – like an expanded CTC – have been underwhelming. As of December 2021, the Build Back Better Act does maintain the fully refundable nature of the expanded-CTC, allowing low- and no-income families excluded pre-pandemic to continue to receive a credit, but only a temporary extension is being considered for the increased amounts families received during the pandemic.

While the Build Back Better Act has not yet passed, the stimulus checks and expanded CTC have moved the needle, breaking down barriers to moving cash policies at any level of government. We now have a much better sense of what is possible when it comes to distributing monthly cash payments, and we have data and stories of the impact these policies have in the lives of low- and middle-income earning families.

In light of the current limits at the local and federal level, there is an opportunity for state governments to explore ambitious, publicly-funded cash transfer policies that:

- promote dignity and greatly improve the lives of their low-income residents;

- add to a growing body of research with assessments of larger scale positive impacts across geographically and racially diverse areas;

- utilize the revenue raising powers of state government; and

- could be a model for a permanent federal program.

We need a permanent federal guaranteed income, but political gridlock and polarization threaten to frustrate attempts at a federal program in the immediate term. States have an opportunity to push closer to that ideal with large scale, publicly funded, permanent programs of their own that will provide essential data and experience toward the realization of a federal program. This guide seeks to arm state-level advocates and policymakers with information regarding the choice points in program design, the positive impacts shown by existing research, and special considerations for states including options for guaranteed income implementation, interactions with existing public benefits programs, opportunities for public funding, and promoting racial equity.

Defining Terms – UBI and GI

Cash transfer policies have taken on a number of names that are sometimes used interchangeably. However, it is important to draw a distinction between two of the most prevalent terms: “universal basic income” and “guaranteed income.”

Universal Basic Income (UBI):

Unconditional, universal cash payments to all members of a community designed to pay for people’s basic needs regardless of income or wealth.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) refers to cash payments granted to all members of a community on a regular basis, regardless of employment status or income level. It is meant to be individual, unconditional, universal and frequent.8 Proposals often seek to provide a payment level that – on its own – is enough to provide for people’s basic needs. Universality is the key feature of UBI. However, because the costs of making a cash payment to every resident strain contemporary conceptions of practicability, UBI proposals would likely require replacing or “cashing out” other federal programs.9 One of the attractions of this model is that a lack of means-testing allows the reduction of complex bureaucracies and regulatory schemes required to determine program eligibility and verify income and assets. UBI proposals are also frequently paired with a “claw-back” of funds provided to higher income earners, as implicit recognition of the need to ensure funds are targeted to those with need.

Guaranteed Income (GI):

Unconditional cash payments that have no work requirements, are targeted to community members with the most need, supplement the existing social safety net, and provide an income floor under which no one can fall.

Guaranteed Income (GI) refers to monthly, cash payment given directly to individuals. It too is meant to be frequent and unconditional, with no strings attached and no work requirements. Guaranteed income is meant to supplement, rather than replace, the existing social safety net.10 Unlike UBI, a guaranteed income is not universal, and prioritizes channeling money to low-income, no-income, and middle-income people.11 Guaranteed income strikes a balance between seeking to eliminate deep poverty while maintaining cost effectiveness and political viability. The most effective cash transfer programs will reduce inequality by targeting lower-income recipients and buttressing, rather than supplanting, existing key programs like SNAP and Medicaid so that people can experience a net gain in resources instead of having them simply replaced by cash.

PoliticsGuaranteed income is effective public policy. And smart politics.

It is impossible to live without cash. A guaranteed income is a direct and effective way to combat poverty and provide stability to people and families with limited resources by ensuring no one can fall beneath a government-issued income floor. Giving people unconditional cash allows them to address their most pressing needs, and available data shows that when people receive cash, they spend it in ways that support themselves and their families.

For example, during the pandemic, research showed that middle- and low-income households spent their CARES Act stimulus checks on food, rent, utilities, mortgage payments, and household supplies.12 This money is not only vital during times of economic distress, but can also promote economic mobility, planning for the future, and investment in self-care.13 Findings from the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration found that recipients spent the guaranteed income on food, utilities, and transportation needs, and that the guaranteed income reduced economic volatility, creating space for new opportunities, self-determination, goal-setting, and risk-taking.14

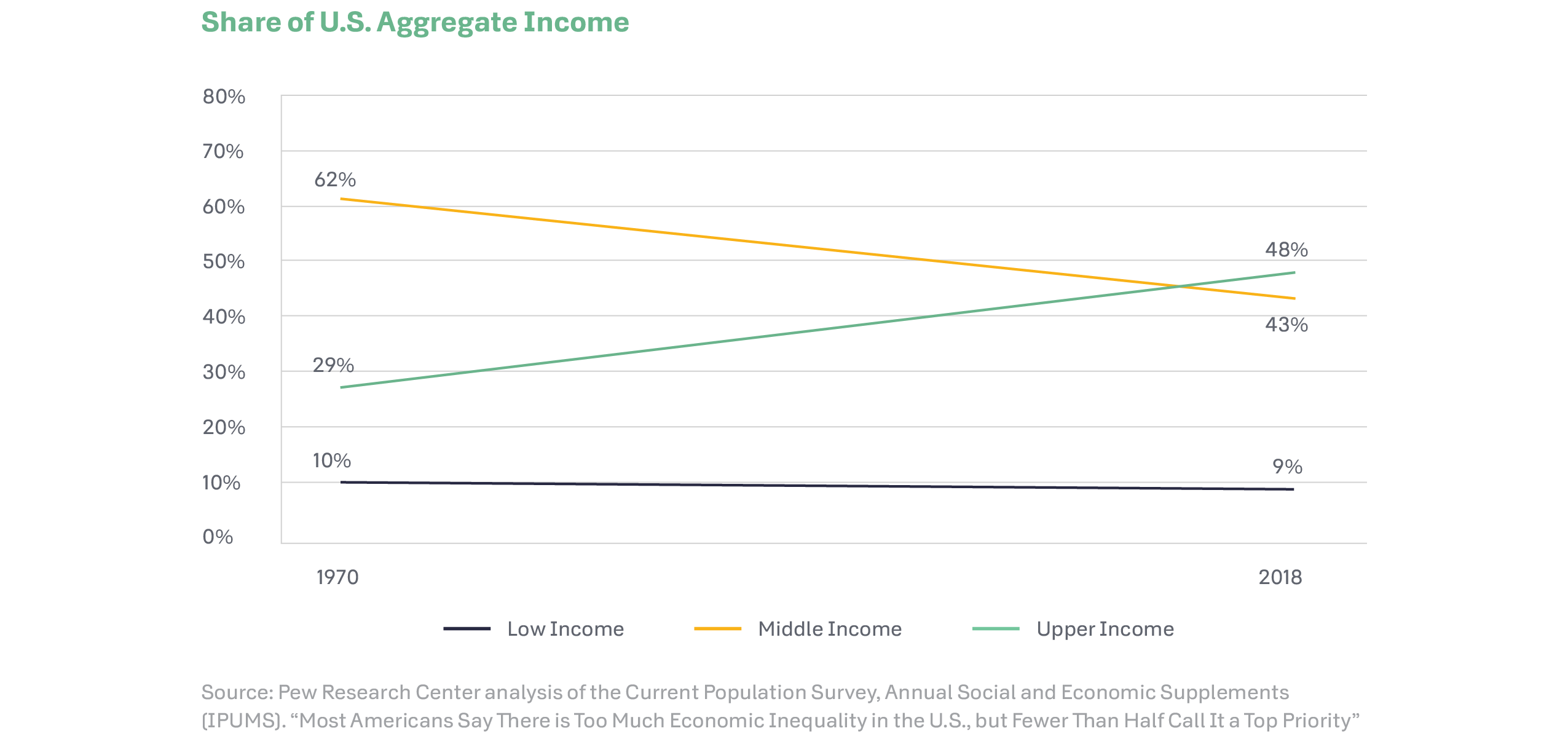

Another positive feature of guaranteed income is the potential to be redistributive and mitigate inequality. Income is a measure of money coming into a household – separate from wealth which measures the value of a household’s assets. While glaring disparities exist in both income and wealth,15 guaranteed income can directly mitigate income inequality and give lower-income families better opportunity to build wealth over time. According to Pew Research Center, from 1970 to 2018 the share of income going to upper-income16 families increased from 29 percent to 48 percent, while the aggregate share of income going to middle-income families fell from 62 percent to 43 percent and the share going to lower-income households fell slightly from 10 percent to 9 percent.17 Further, the top 5 percent of earners experienced the greatest rate of income growth over the same period.18 This untenable disparity represents investment in structures that exploit low- and middle-income households for the purpose of funneling greater income to the richest individuals. A guaranteed income can rebalance this structure.

As discussed in greater detail below in A Guaranteed Income Can Promote Racial Equity, guaranteed income alone is insufficient to build racial income and wealth equity. However, creating an income floor through which no one can fall would disproportionately benefit Black, Indigenous, and Latino/a/x individuals who have been consistently locked out of higher wage earning positions due to centuries of discriminatory policies and practices.19

A guaranteed income funded by increasing the tax burdens on both wealth and income for the wealthiest and highest income taxpayers and corporations and targeting that redistribution to lower income tiers or those without income, can represent a massive step in reversing ever-rising income inequality. However, addressing wealth inequality could warrant additional interventions. While increasing a household’s income can create greater opportunity to build wealth, states could also consider policies that more directly address wealth inequality.

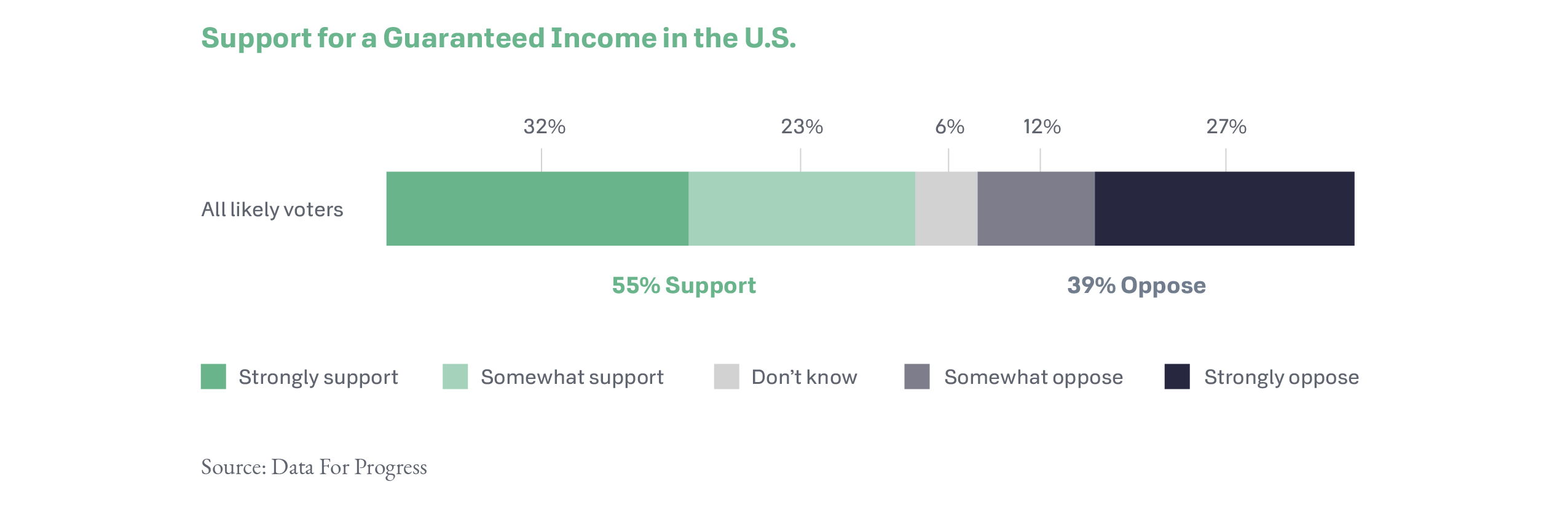

Lastly, cash transfer programs, such as guaranteed income, are widely popular. A 2021 survey by Data for Progress found that a majority of likely voters support a guaranteed income policy in general, as well as the guaranteed income provided through the expanded-CTC. Voters supported a guaranteed income by a 16-point margin (55 percent support; 39 percent oppose), and support was particularly strong among Black and Latinx voters, who supported a guaranteed income at 79 and 74 percent, respectively.20

Existing state cash transfer programs are also popular. Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) is funded through the state’s oil extraction revenue and is the most robust cash transfer program in any state across the country. Since 1982, a dividend has been paid to all Alaska residents who resided in the state for the entirety of the previous year and intend to remain indefinitely.21 In 1984, shortly after the program was created, about 60 percent of Alaskans thought the Permanent Fund Dividend Program was a good idea.22 In a 2017 survey conducted by the Economic Security Project, nearly 4 out of 5 respondents had positive attitudes toward the PFD (including 59 percent very positive) to only 7 percent negative. The same survey found that nearly 4 out of 5 Alaska voters felt the yearly dividends have made a difference in their lives over the past five years. By an overwhelming margin of 85 percent to 7 percent, Alaskans agreed that, “many people spend a large part of their PFDs on basic needs.23

Guaranteed income is effective public policy because it supports people in meeting their basic needs and has tremendous potential to decrease sharply rising income inequality.

Further, different forms of cash relief were overwhelmingly popular during the pandemic including expansion of the CTC, and direct stimulus payments.24 For example, in two highly consequential Georgia Senate runoff races in early 2021, 87 percent of Georgia runoff voters demanded more $1,200 checks, with 63 percent saying they were more likely to support a candidate who backed more checks.”25

Guaranteed income is effective public policy because it supports people in meeting their basic needs and has tremendous potential to decrease sharply rising income inequality. Moreover, available polling shows that cash transfers like a guaranteed income are popular and that people across the political spectrum believe they are

worthy of pursuit.

Characteristics of Guaranteed Income Programs

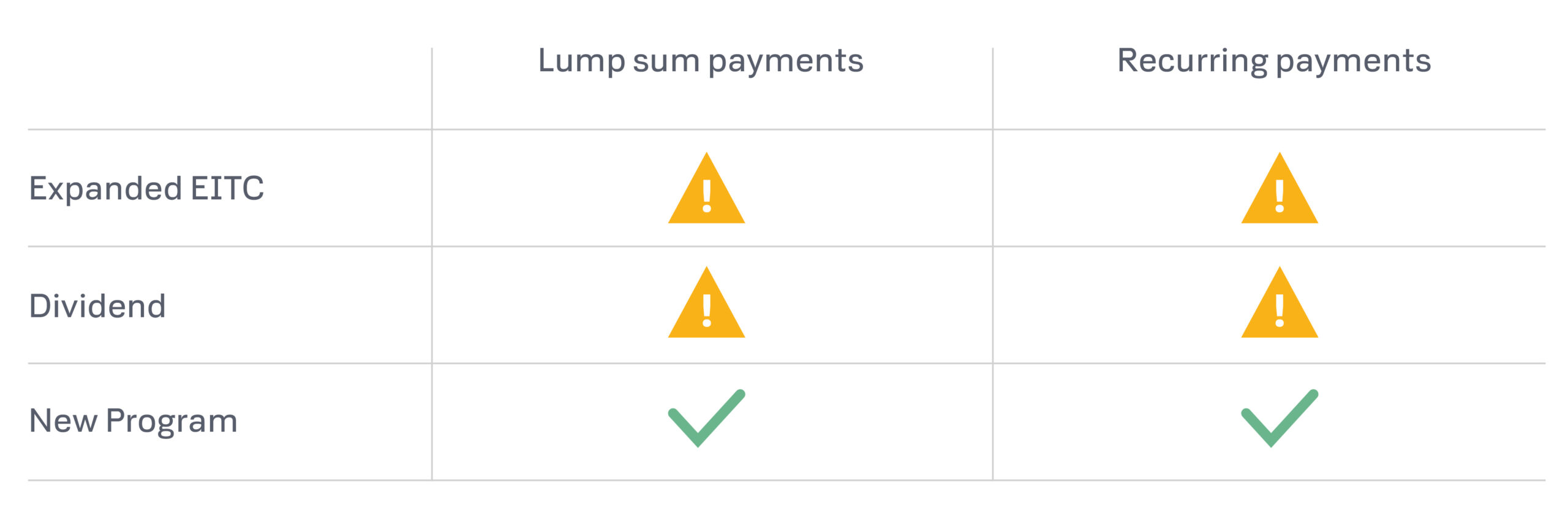

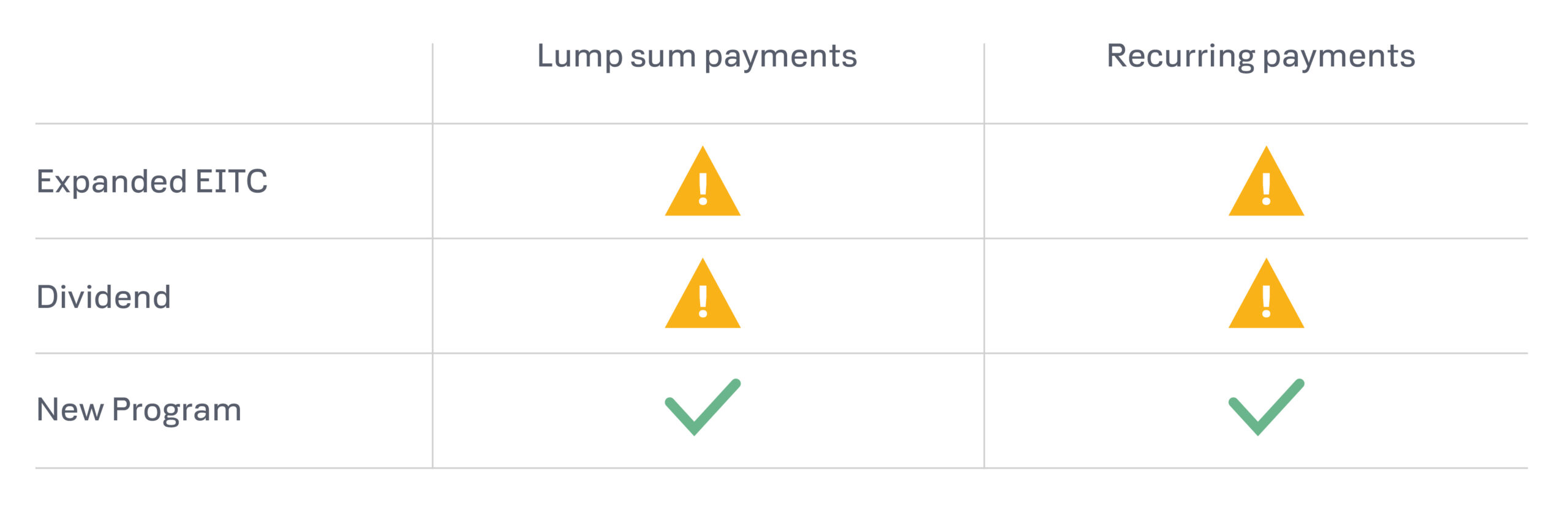

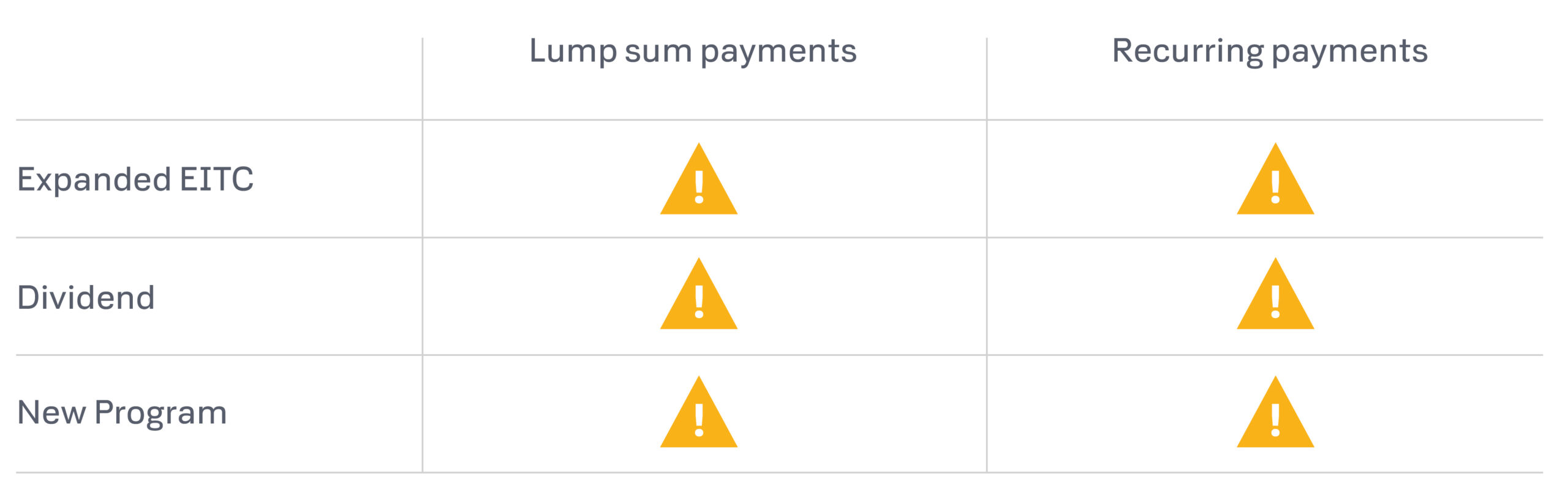

Advocates for guaranteed income have an array of choice points in program design. While guaranteed income programs have chosen eligible low-income participants based on the characteristics of a target population (e.g. Black mothers in living in public housing or unhoused youth) or residence in a particular geographic area, the breadth of permanent state programs will largely depend on program cost and mechanisms for raising revenue to meet that cost. States also have an opportunity to think creatively about different implementation strategies that utilize existing state infrastructure to deliver cash to eligible individuals – such as enacting or expanding a state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) or Child Tax Credit (CTC). Whether a state chooses to build a new program or implement a large-scale guaranteed income through an expanded EITC, either method could have implications for how payments interact with existing social safety net programs. There are also a host of choices around payment level and payment frequency that may have implications on existing benefits. Below is a table showing a high-level depiction of program design from a relevant cross-section of cash transfer programs that have produced meaningful data on how a guaranteed income could impact recipients.26

Features of Guaranteed Income Models

Program/ Demonstration: Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) – AK (state-wide) (1982 – present)

Size: Estimated 643,000 recipients in 2021

Eligibility:

- Must have been a resident of Alaska for the entire previous calendar year and intend to remain indefinitely as of the date of application.

- Status Requirement: Must be a U.S. Citizen, LPR, refugee, or asylee.

- Some residents with current or previous criminal legal involvement are excluded

from eligibility. - Eligibility Requirements

Funding:

- Public – Dividend Paid from Alaska’s Permanent Fund which contains revenue raised from state oil extraction.

- $1B disbursed in 2019

- $625M disbursed in 2020

Amount:

- $1114 (2021)

- $1168 (average)

- $331 (lowest – 1984)

- $2069 (highest – 2008)

- Table of payments since 1982

Frequency: Lump-sum paid once annually in October.

Duration: Ongoing since 1982

Effects on Other Benefits:

- Medicaid: PFD excluded from consideration as income or resources for all mandatory and optional Medicaid categories.

- SNAP: PFD counts as unearned income and a resource in the month received. Federally granted waivers allow cases to be suspended for up to four months when the PFD makes a household ineligible or reduces a categorically eligible household’s benefit to zero.

PFD Hold Harmless benefit issued to households who lose SNAP eligibility. - SSI: PFD counts as income and a resource. Recipients are overpaid by SSA, and SSA sends an overpayment bill to the state every year. State’s Hold Harmless program pays the recipients overpayment.

- ATAP (TANF): PFD payments and Hold Harmless Payments are exempt as income.

Additional Resources:

- 2016 Study – Inst. Of Social and Econ. Research, Univ. of AK Anchorage

- 2019 Study – Inst. Of Social and Econ. Research, Univ. of AK Anchorage

Program/Duration: Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED) – Stockton, CA (2019)

Size: 125 participants

Eligibility: Must be: 1) at least 18 years old; 2) a resident of Stockton, CA, and, 3) living in a neighborhood with area median income below $46,033.

Funding: Private Donations, $1.5M in payments

Amount: $500

Frequency: Monthly

Duration: 24 months

Effects on Other Benefits:

- See. Baker, A. C., Martin-West, S., Samra, S., & Cusack, M. (2020). Mitigating loss of health insurance and means tested benefits in an unconditional cash transfer experiment: Implementation lessons from Stockton’s guaranteed income pilot. SSM – population health, 11, 100578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100578

- MediCal (Medicaid) – payment is a gift from a non-profit that is not taxable by the IRS and thus not counted as income.

- CalFresh (SNAP) – Considered unearned income that could impact eligibility and benefit amount.

- SSI – Counts as income and a resource and may affect eligibility.

- CalWorks (TANF) – Income exempted through waiver by San Joaquin County Health Services Agency.

- Section 8 (HCV) -Recipient share-of-cost does increase, impacting rent amount, but is reimbursed by the Hold Harmless Fund established by SEED.

Additional Resource: Preliminary Analysis of First-Year (2019)

Program/Demonstration: Magnolia Mother’s Trust – Jackson, MS (2020 – present)

Size:

- 1st cohort – 20 (Dec. 18’ – Nov. 19’)

- 2nd cohort – 110 (Mar. 20’ – Feb 21’)

- 3rd cohort – 100 (Apr.21’ – Mar. 22’)

Eligibility: Target population: Households headed by Black women living in federally subsidized housing projects in Jackson, MS.

Funding: Private donations, $2.76M in payments

Amount: $1000

Frequency: Monthly

Duration: 12-months

Effects on Other Benefits:

Benefits not protected.

- During the pilot, some mothers experienced a reduction in benefits, such as SNAP,

(e.g. one mother’s SNAP was reduced from $500 to $200) See here. (pg. 7) - Some mothers experienced decrease or loss of SNAP benefits and increase in share

of rent.

Additional Resources:

- Magnolia Mother’s Trust Two-Pager

- 2020 Evaluation

- Aspen Inst. Report

Program/ Demonstration: MINCOME – Manitoba, Canada (1975 – 1979)

Size: 1000 households

Eligibility:

- Families selected from two experimental sites: Winnipeg and the rural community of Dauphin in western Manitoba. A number of small rural communities were also selected to serve as controls for the Dauphin subjects.

- Dauphin (pop. 100K) was a “saturation site” where every family in the city was eligible

- Must have household income under $13,000, head of household must be under 57 years old, and household members must not be struggling with a physical or mental disability. Other exclusions applied. See here.

Funding:

Public funding: 17 million (75%) appropriated by Canadian federal government. Province paid 25% of the cost.

Amount:

- A family with no income gets 60 percent of the Statistics Canada low-income cut-off (LICO), which varied by family size.

- Every dollar of income from other sources would reduce the payment by 50 cents.

Frequency: Annual payment using negative income tax approach

Duration: 4 years

Effects on Other Benefits:

- Families with no other income who qualified for social assistance would see little difference in their level of support, but for people who did not qualify for welfare under traditional schemes—particularly the elderly, the working poor, and single, employable males—MINCOME meant a significant increase in income.

- Goal was for the lowest payment level to “yield an acceptable degree of domination over the existing welfare programs.” See here

Additional Resources:

- Analysis of health Impacts

- MINCOME technical manuals

Positive Impacts of Cash

Research from guaranteed income pilots (and a growing body of research around the spending of pandemic relief) show that when low-income people receive money, they spend it to meet their basic needs. For instance, spending on food and housing far exceeds other areas of expenditure. Guaranteed income raises the floor so people can live with dignity. It also empowers individuals to make a greater array of choices, focus on personal growth, plan for the future, and be the best versions of themselves at work, at home, and in their community. Existing data on guaranteed income programs which clearly show a range of positive impacts on economic stability, employment, physical health, mental health, nutrition, and education.

Economic Stability

- The Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) program has lifted 15,000 to 25,000 Alaskans out of poverty every year depending on the size of the payment and fluctuations in the state economy in a given year. An estimated 25 percent more Alaskans would fall below the poverty line without it. In 2000 alone, the PFD reduced poverty by 40 percent (6.4 percent from an estimated 10.6 percent without the PFD), and it’s estimated that 25 percent more Alaskans would be in poverty every year without it.27

- In the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED), guaranteed income participants experienced 1.5 times less month-to-month income volatility—for those receiving payments, income fluctuated by 46.4 percent monthly while the control group experienced a 67.5 percent monthly income fluctuation. The number of recipients able to pay cash for an unexpected expense increased from 25 percent to 52 percent.28

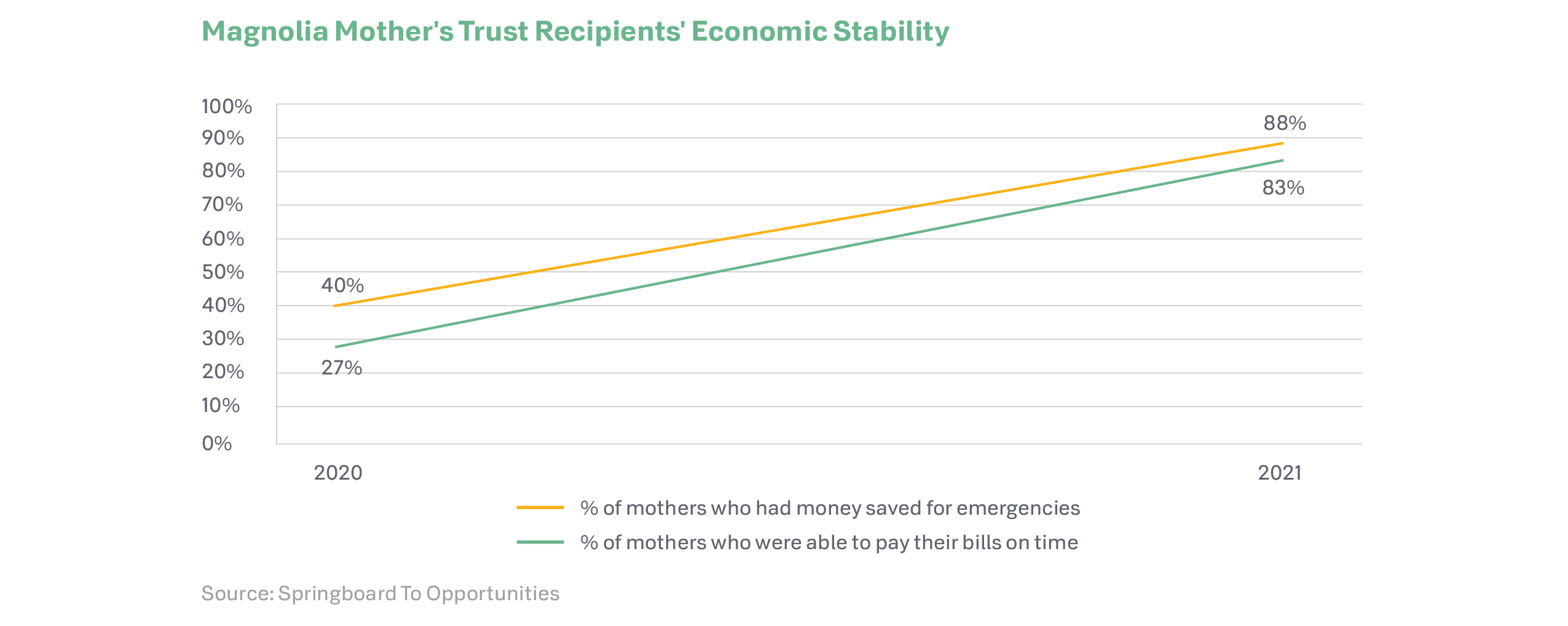

- In the Magnolia Mother’s Trust program, the ability of mothers to pay their bills on time increased from 27 percent to 83 percent. The percentage of mothers who had money saved for emergencies increased from 40 percent to 88 percent and more mothers reported having saved for college and retirement. Additionally, mothers with life insurance increased by 37 percentage points (50 percent to 87 percent) suggesting an ability to plan for the long-term financial security of their children.29

Employment

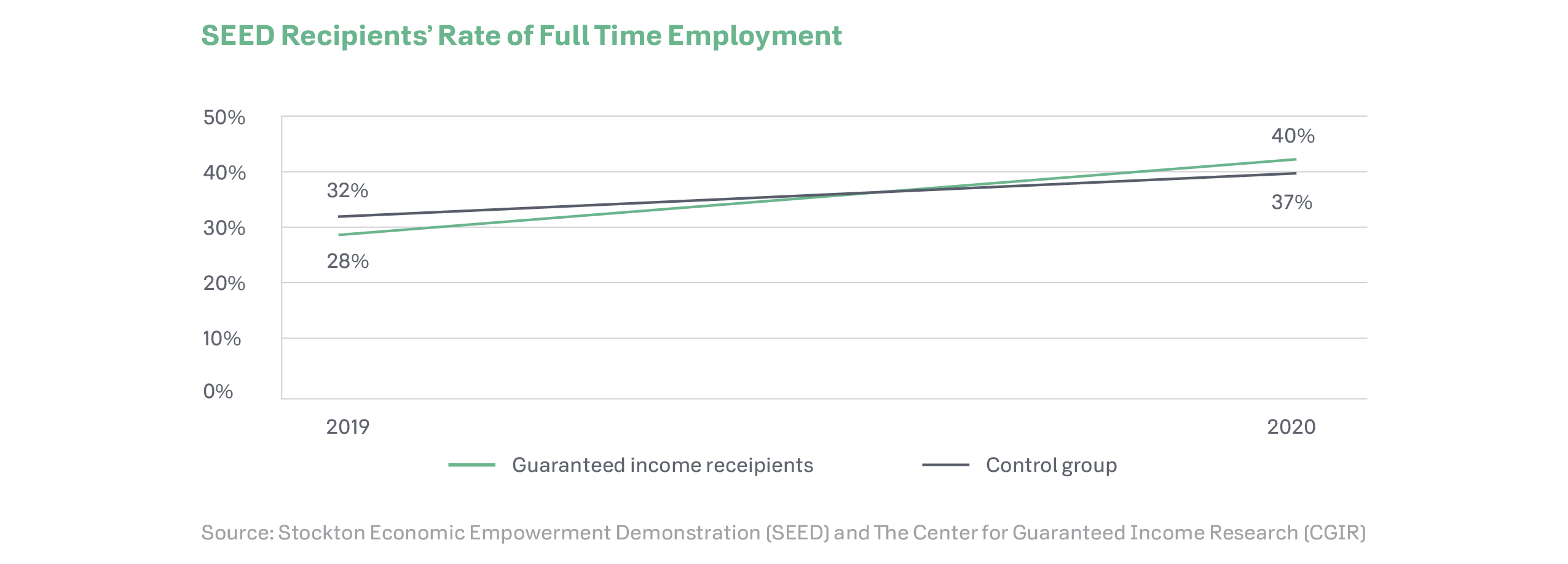

- The Stockton SEED results showed an increase in full-time employment from 28 percent to 40 percent. Researchers also observed an increase in participants’ ability to pursue internships, training, or coursework that could lead to better jobs or a promotion. Further, recipients had more capacity for goal setting and risk-taking, contributing to upward mobility in the labor market.30

- Magnolia Mother’s Trust participants reported that the money gave them the ability to choose jobs with flexible hours to accommodate family schedules and support their children’s virtual learning during the pandemic. This led to an increase in school attendance from before the start of the program, despite the significant challenges with virtual schooling during the pandemic.31

Physical Health

Magnolia Mother’s Trust participants’ ability to see a doctor for an illness increased from 40 percent to 70 percent and health insurance coverage rates increased 25 percent. Mothers also experienced a decrease in medical debt from out-of-pocket expenses.32

In Dauphin, Manitoba – the saturation site for the province’s MINCOME experiment, hospitalization rates fell by 19.23 per 1,000 residents over five years.33

Alaska PFD researchers estimated that an additional $1,000 in dividend payments increases birth weight by 17.7 grams, and substantially decreases the likelihood of a low birth weight by 14 percent.34

Mental Health

Magnolia Mother’s Trust participants reported an increase in positive family engagement and feeling hopeful about their future in five years. Mothers also described being able to engage in more self-care activities.35

Stockton SEED recipients indicated that the payments had positive effects on their mental health. Recipients reported reduced stress and anger, increased sleep, and increased enjoyment of and time spent with family. Participants also experienced significant improvements in anxiety and depression when compared to themselves at baseline, moving down the Kessler 10 scale36 from “likely having a mild mental health disorder” to “likely mental wellness” over the course of the year.37

Nutrition / Food Security

Magnolia Mother’s Trust participants reported an increase from 64 percent to 81 percent

in their ability to have enough money for food, and saw a 43-percentage point increase

in the proportion of those who prepared three meals a day for their families (32 percent

to 75 percent).38

Alaska PFD researchers found that payments contributed to reduced obesity and overweight status for children, and further estimated an additional $1,000 in PFD

payments would result in a 22.4 percent reduction in the number of obese three-year-olds.39

Stockton SEED recipients were better able to afford the food they needed. The biggest expenditure each month was food, which made up approximately 40 percent of

tracked purchases.40

Additional Positive Impacts

The Magnolia Mother’s Trust payments resulted in a 22-point increase in the number of mothers who completed high school.41 Transportation is also critical to maintaining employment. During the second cohort of the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, the number of mothers reporting they always had gas in their car when they needed it increased from 55 percent to 82 percent and those who had car insurance coverage increased from 50 percent to 86 percent. Furthermore, the percentage of participants with a vehicle also increased from 75 percent to 88 percent.42

State Considerations: Implementation Strategies

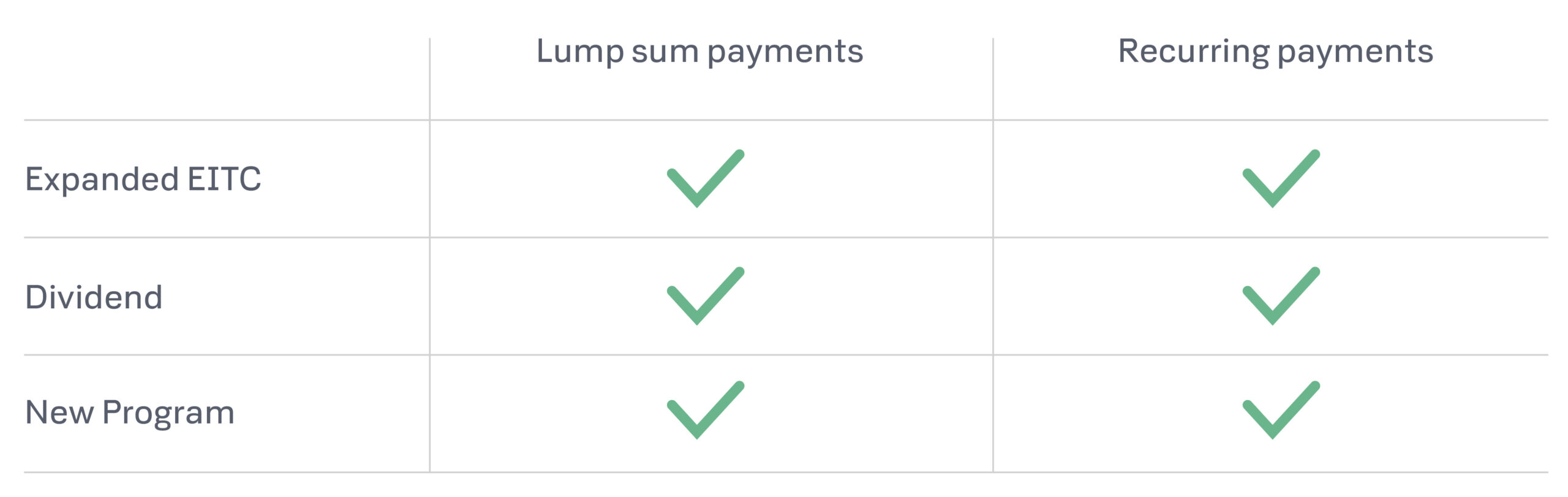

As states consider the creation of a large-scale, publicly-funded guaranteed income program, they need to choose how to implement the program. Implementation strategies do not merely affect overall program cost and administration, but they are also highly relevant in determining how publicly-funded guaranteed income payments interact with other means-tested public benefits.

States can choose to adopt one of the following implementation strategies:

- Use the tax system by implementing or expanding a state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) or Earned Income Credit (EIC).

- Create an invested public sovereign wealth fund and declare periodic dividends for eligible households (similar to Alaska’s program).

- Construct robust new infrastructure to administer the program, or, at the very least, integrate the program into existing benefit distribution processes.

Expanding State Earned Income Tax Credit

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax credit for working families created in 1975 by the Ford Administration. Its aim was to shield low-wage workers from the regressive effects of rising payroll taxes and to provide an additional income boost for workers near or below the poverty line.43 While the majority of an individual’s EITC comes from their federal tax return, thirty states, the District of Columbia, and a few municipalities44 have established their own EITCs to supplement the federal credit.45

Similar to the recently expanded federal Child Tax Credit, what distinguishes the federal EITC from many other credits in the tax code is its ”refundability,” meaning the full amount of the credit is given to low-income workers as cash, rather than merely reducing their tax liability. In 2018, the federal EITC lifted roughly 5.6 million people out of poverty, including about 3 million children. A state approach that modifies and bolsters a state EITC to achieve a functional guaranteed income for low-income people is an attractive proposition because it both comes with an existing mechanism to get payments to recipients, and those payments have a stronger basis for exemption from consideration as income in other benefits programs

like SNAP and TANF.

Unfortunately, the current federal EITC framework does not provide the full credit to households that do not meet the minimum threshold of earnings to qualify, excluding the lowest wage earning and non-wage earning households. Additionally, some groups like unpaid caregivers and domestic workers, as well as immigrants who file taxes with an Individual Tax ID number are not able to access these valuable credits. A state could create an efficient avenue to a functional guaranteed income for a large swath of a state’s population by enacting reforms to the state EITC that:

- Is fully refundable, ensuring that extremely low- and no-income families are eligible,

- Expands the state’s federal match rate to provide recipients with greater support,

- Raises income eligibility thresholds to extend eligibility to some middle-income earners, and

- Provide access to immigrants and other previously excluded groups.46

Dividend from an Invested Public Fund

$1600

Average annual amount Alaska residents from the Permanent Fund since 1980

Another model for statewide implementation of a guaranteed income would be declaring periodic dividends from a state government managed sovereign wealth fund. One prominent example is the annual dividend from Alaska’s Permanent Fund. After oil was discovered in Alaska in the 1960’s, the Prudhoe Bay Oil and Gas lease sale in 1969 brought in $900 million in state revenue.47 Following the completion of the Trans Alaska Pipeline in 1974, the state grappled with how to invest its anticipated oil royalties. In 1976, Alaska residents voted to amend the state’s constitution to allow the creation of the Alaska Permanent Fund, in which at least 25 percent of all the state’s oil revenue would be placed.48 The following year, the Fund began with an initial deposit of $734,000. In 1980, a state law created the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation to invest and manage the fund while also creating the Permanent Fund Dividend Program which has paid Alaskans an average of $1600 annually.49 Since 1980, the fund has grown exponentially from its initial investment with a 2021 value of nearly $82 billion.50 Administered by the state’s Department of Revenue, every year each Alaskan submits an application, largely to verify their residence in the state, and then receives a check in an amount determined by the state legislature based, in part, on the performance of the fund’s investments. Although the Permanent Fund Dividend is distributed to Alaska residents regardless of their wealth or income, other states could conceivably embrace a guaranteed income model over a universal model and create income and wealth thresholds for determining eligibility for dividend payment.

A number of states have sovereign wealth funds like the Alaska Permanent Fund that originated from natural resource revenue or public land holdings. Texas, New Mexico, Wyoming, North Dakota, Alabama, Utah, Oregon, Louisiana, and Montana, all have funds, most of which are used to fund public education. States could establish funds like these to grow wealth for the purpose of a state-level guaranteed income.

While most current models began with investment of revenue from natural resources, annual investments into a state fund could also be powered by equitably raised tax revenue.

It is worth noting that the sovereign wealth fund model may weaken a publicly-funded guaranteed income program’s potential to be redistributive – shrinking income inequality by raising tax burdens on wealthy individuals and corporations and distributing it to those at the bottom of the income hierarchy. Investing large sums of public money in sovereign wealth funds could undermine this objective if the best strategy for growing the fund is investment in large corporations, “blue-chip-stocks”, and private equity firms.51 Such an approach could perpetuate the funneling of money upward on the income spectrum, and further harm the environment by encouraging investment in unsustainable extractive industries like oil and natural gas.

Building a New Program

States can also lean on their existing benefits-granting agencies to administer a guaranteed income alongside other core means-tested programs like SNAP, TANF, and Medicaid. For example, in California, the Department of Social Services (“Department”) is funding new guaranteed income programs created by units of local government and other eligible entities.52 In 2021, the California state legislature added $35 million to the state budget to fund guaranteed income demonstrations over the next 5 years, prioritizing funds to pregnant mothers and youth aging out of the extended foster care system at or after age 21.53

The Department will accept applications from entities seeking to create a program, and will work with stakeholders to create program methodologies, select mechanisms for payment distribution, and establish

a process by which recipients can receive counseling on the impacts of receiving a guaranteed income on other benefits.

Unlike the majority of states, California utilizes a county-based benefits system that delegates administration of programs like CalFresh (SNAP), CalWORKS (TANF), and Medi-Cal (Medicaid) to county governments. With this benefits administration structure, therefore, it is consistent for California to lean on counties as units of local government to create guaranteed income programs subject to approval by the state. However, states who utilize state-based benefits administration could use a similar method of creating a new state-level guaranteed income program and administering it through state-run local offices that already oversee SNAP, TANF, and Medicaid.

A potential advantage of creating a new guaranteed income program administered by traditional benefits granting agencies is the potential for information sharing. Because a guaranteed income is targeted based on income level, some data showing an applicant’s income will be necessary to assess eligibility. For many no- and-low-income households who may be accessing benefits, the agency may already have information needed to assess eligibility for a guaranteed income and could adopt a system of “categorical” or “express lane” eligibility – where participation in one means-tested program verifies income eligibility for guaranteed income, and makes application processing easier.54 A new guaranteed income program could also be integrated into combined applications for benefits, allowing applicants’ eligibility for multiple programs to be assessed at once. Lastly, benefits granting agencies may be better positioned to assess and relay the potential consequences of guaranteed income receipt on other benefits.

Benefits ProtectionState Considerations: Benefits Protection

A guaranteed income intended to boost the economic security and well-being of recipients while reducing inequality will supplement the existing social safety net rather than replace it. A feature of the social safety net is that many programs are “means-tested” meaning that eligibility for receipt of a particular benefit (such as nutrition or medical assistance) is determined by assessing whether a person or household has the means (income and resources) to meet basic needs without assistance.55 Because of means-testing, any additional income from a guaranteed income program could impact eligibility for other programs. As such, advocates and state decisionmakers should pay careful attention to how an infusion of cash could affect guaranteed income recipients’ eligibility for other means-tested benefits programs such as SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and housing benefits.

A guaranteed income intended to boost the economic security and well-being of recipients while reducing inequality will supplement the existing social safety net rather than replace it.

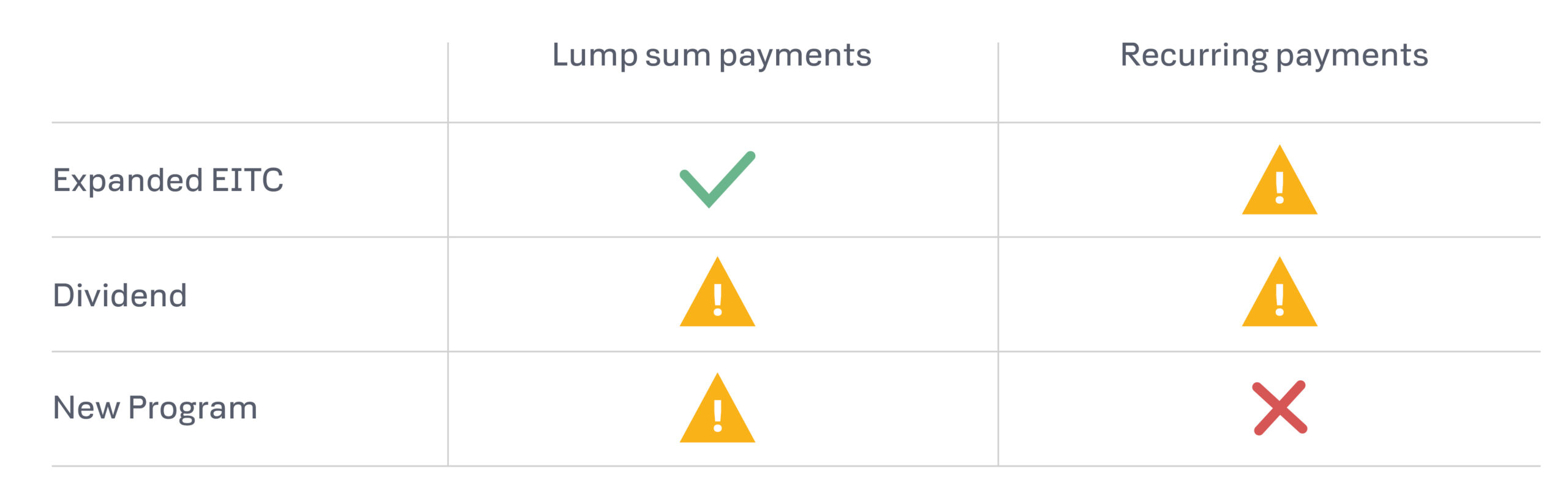

Administrators of privately funded guaranteed income demonstrations have been able to work with state and local agency officials to ensure benefits-granting agencies characterize guaranteed income payments in a way that does not threaten eligibility.56 However, in some cases, excluding guaranteed income payments from consideration becomes more challenging if those payments are publicly funded. Other relevant factors include the frequency with which payments are received and the state’s implementation strategy.

Where benefits eligibility is threatened, states can learn from mitigation strategies adopted by existing guaranteed income models. Some demonstrations have addressed the risk to other means-tested benefits by partnering with trained public benefits counselors who help recipients navigate the byzantine rules of these systems. Other programs – including the Alaska PFD – have established a Hold Harmless Fund that seeks to replace the value of any benefits lost because of the cash received.

The following subsections examine the potential for excluding publicly-funded guaranteed income programs from consideration in eligibility for TANF, SNAP, Medicaid, and federal housing benefits depending on the chosen implementation strategy and the frequency of the payments. Although the focus of these analyses is the application of federal law, in many contexts, states have the ability to further expand or restrict access to benefits. In some instances, federal law may provide flexibility for the exclusion of certain guaranteed income payments from consideration in income eligibility, but states have either forbid the use of, or chosen not to exercise, such flexibility. While this guide can serve as a useful starting place for state-level stakeholders, the Alaska PFD represents the only precedent for large publicly-funded state cash transfers resembling a guaranteed income. As such, there may be some areas where additional action or guidance from federal agencies will be required to ensure benefits protection.

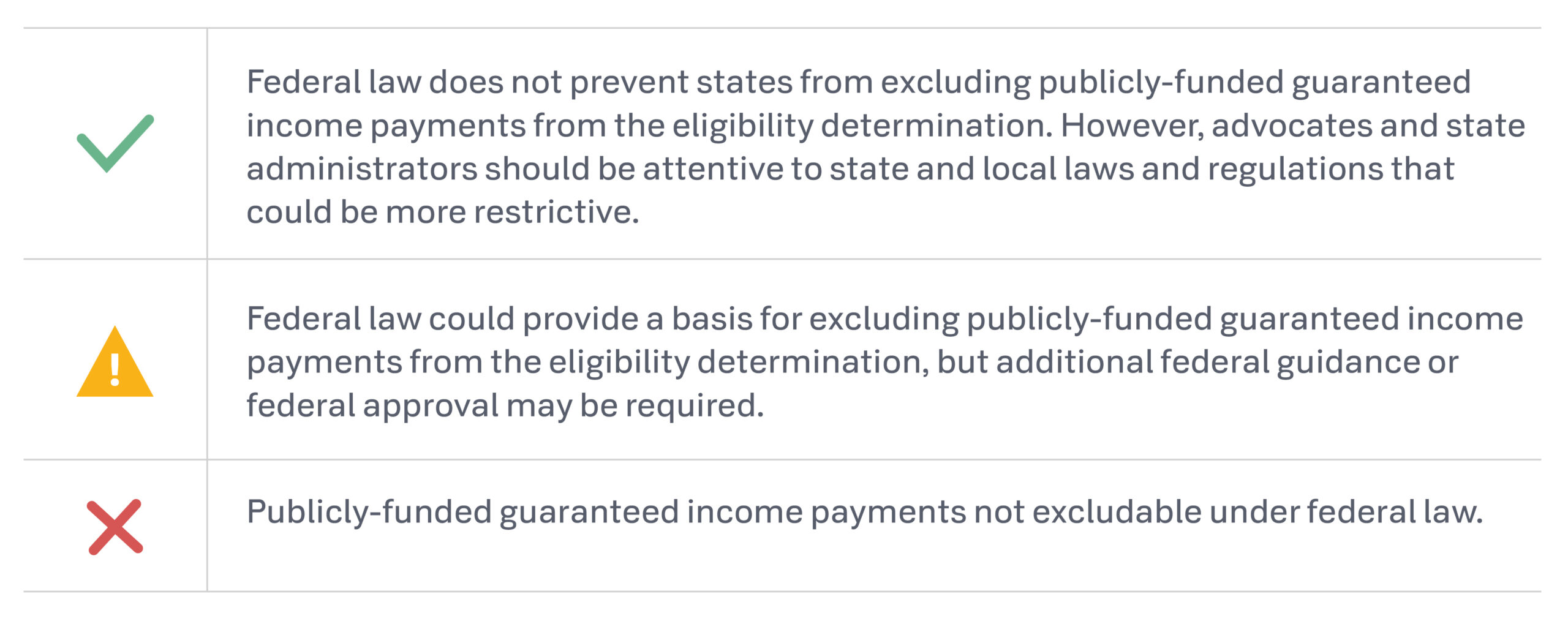

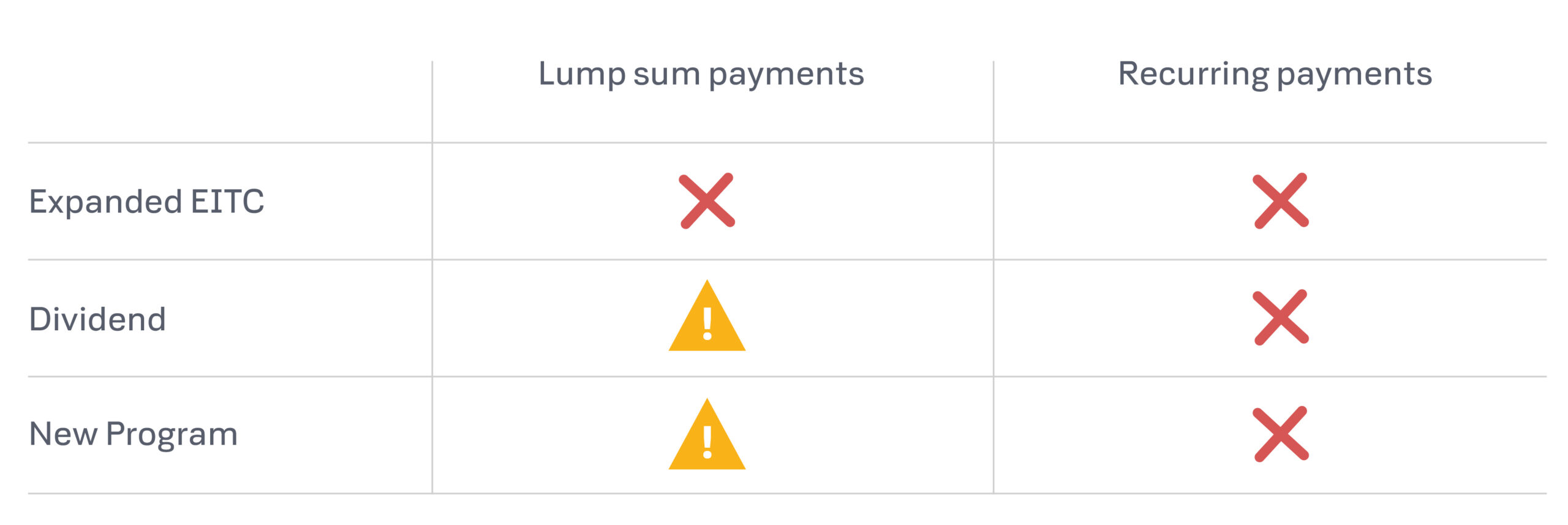

Symbol Key

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

Federal law does not define income or assets for TANF purposes.57 As such, states have broad discretion to define income and eligibility for TANF cash assistance, resulting in a wide variety of TANF eligibility thresholds and payment levels between states. Federal law would not prevent publicly funded guaranteed income payments from being excluded in the income and asset eligibility determinations for a state’s TANF program – regardless of the implementation strategy or payment frequency.

Importantly, state laws or regulations could prevent such an exclusion. Some states, such as Illinois, have addressed this by passing state laws that would exclude payments as part of a guaranteed income research project from consideration in TANF. Others, like Louisiana, were able to make such exclusions through changes to state regulations. States should evaluate how the current state structure of countable income and eligibility in their TANF cash assistance program could be impacted by an infusion of cash.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

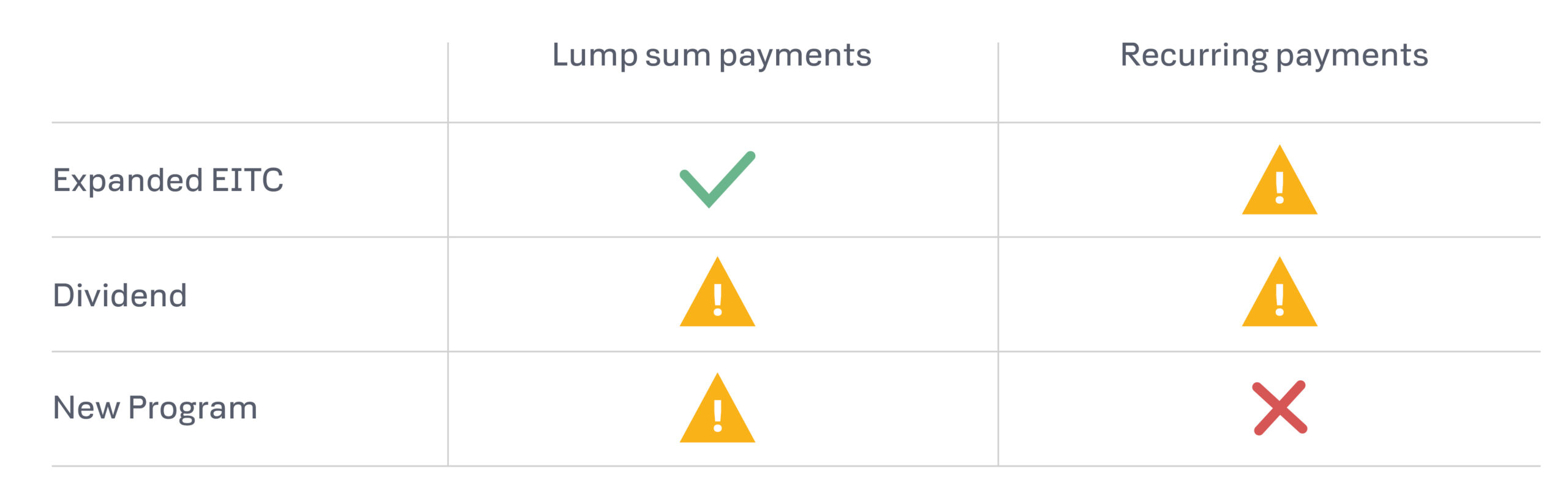

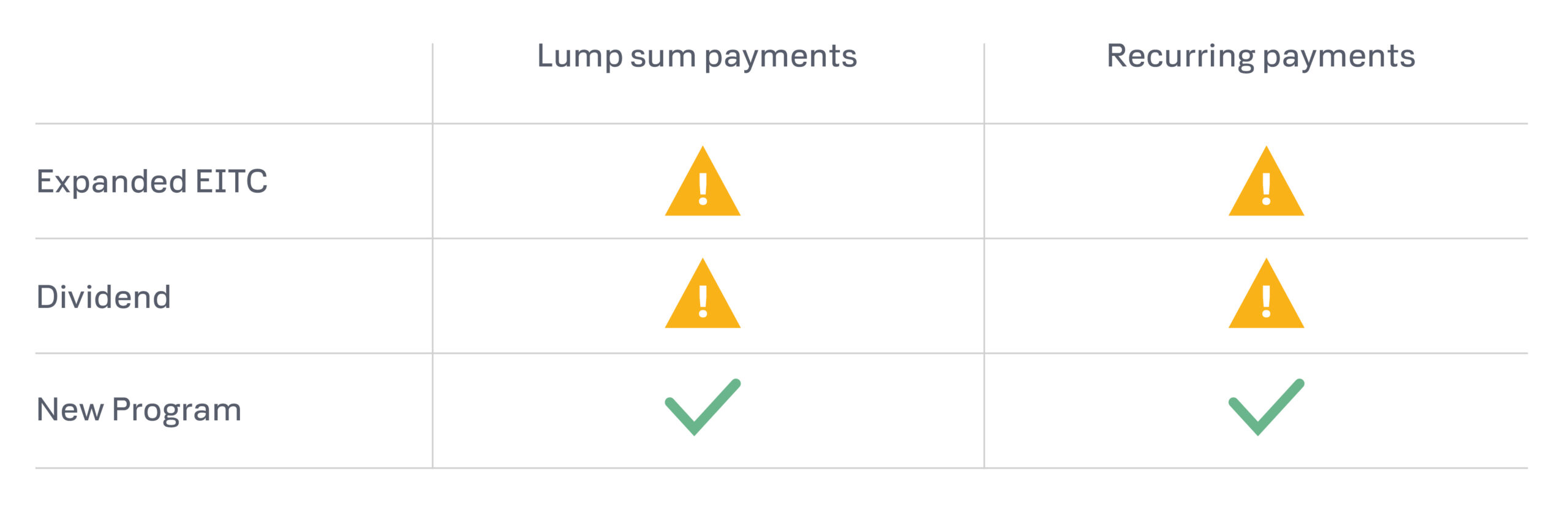

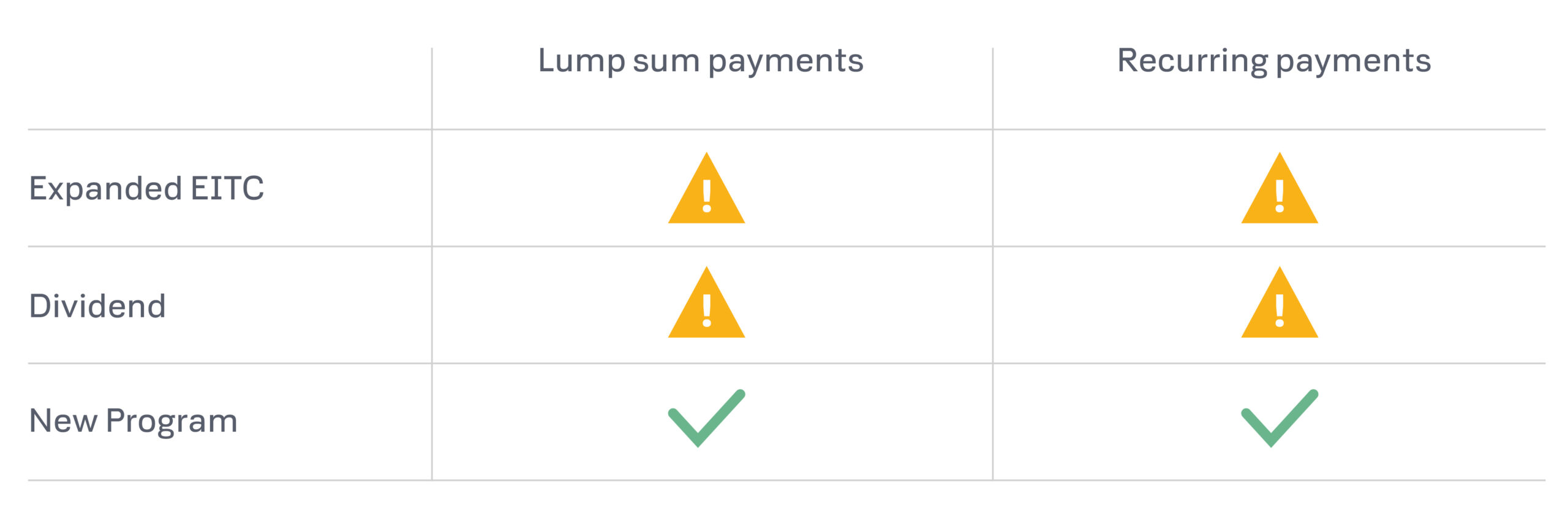

A state’s implementation strategy could be dispositive with regards to protection of SNAP benefits. For states choosing to implement a guaranteed income through state EITC expansion, federal law provides a strong case for exclusion of these payments from the income eligibility determination in SNAP, especially if paid as a lump sum.58 However, SNAP’s income exclusion for state and local tax refunds and credits seems to be predicated on the credits being non-recurring, so models that seek to deviate from lump-sum payments in favor of periodic payments may put SNAP eligibility at risk. For those seeking to implement a “dividend” model, treatment of Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend is instructive. Alaska counts the Permanent Fund Dividend as both unearned income and a resource/asset. To mitigate the impact of the PFD on SNAP eligibility, Alaska set up a Hold Harmless Fund to pay benefits to families who lose eligibility because of the PFD, and receives waivers59 from the federal government allowing them to temporarily suspend SNAP cases for up to four months until eligibility is regained, so the state does not have to terminate the SNAP case and force recipients to re-apply. Lastly, for states building a new program, recurring payments administered through this method will likely jeopardize SNAP eligibility. Some privately funded demonstrations have been able to exclude payments from being included in SNAP, but the same provisions that relay this flexibility cannot be used for regular payments from a government source,60 and exclusion of lump sum payments through this model may depend on USDA’s interpretation of “non-recurring.”61

For more detail on interactions with SNAP see Appendix B.

Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) Medicaid

Except for some specific populations, Medicaid generally uses MAGI (Modified Adjusted Gross Income) as defined by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to determine eligibility. Importantly, the IRS does not count as income “governmental benefit payments from a public welfare fund based upon need.”62 As such, a publicly funded guaranteed income paid as part of a new program or as a “dividend”63 from a sovereign wealth fund that is targeted to individuals based on income would likely be exempt. States seeking to implement a guaranteed income via expansion of a state EITC may encounter complications with MAGI Medicaid eligibility. Unlike federal tax refunds and credits,64 state tax refunds, as well as state credits and offsets, are included by the IRS as taxable income if the tax filer claimed an itemized deduction on their federal tax return for state taxes that were later refunded. Guaranteed income recipients should be advised of potential impacts of tax choices to ensure that MAGI Medicaid program eligibility will not be affected. While some benefits such as SNAP could be replaced by a Hold Harmless Fund, there is no suitable cash replacement for health insurance coverage.

For more detail on interactions with MAGI Medicaid see Appendix C.

Non-Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) Medicaid

There are some categories of individuals who are non-MAGI, such as those who are over 65, blind, or disabled. For these groups, Medicaid eligibility is generally determined using the income methodologies of the SSI program.65 For non-MAGI cases, assistance based on need that is wholly funded by a state or one of its political subdivisions does not count as unearned income and would not be considered in determining eligibility. As such, a guaranteed income implemented as part of a new program, or a “dividend” would likely not affect non-MAGI Medicaid eligibility so long as the payments are targeted to individuals based on income level.66 For states implementing through an expanded EITC, there appears to be discretion with how to treat state tax credits and refunds in the income eligibility determination. For example, in Illinois, state tax refunds are counted as an asset for non-MAGI eligibility, but the portion of the state tax return that is from an earned income credit is not to be included as either an asset or as income.67 In order to protect eligibility for non-MAGI Medicaid, states should use any available flexibility to exempt state EITCs from consideration, should they choose that strategy for implementation of a guaranteed income.

For more detail on interactions with non-MAGI Medicaid see Appendix C.

Housing Benefits

For the three largest housing programs – Housing Choice Vouchers (Section 8), Project Based Rental Assistance, and Public Housing68 – income determinations affect both income eligibility and the amount of rent recipients pay. Generally speaking, all three programs rely on the same federal regulations for determining income. There is an income exemption for non-recurring income that is neither frequent or reliable, but HUD guidance suggests that even payments made only once a year could still be counted if the family expects to receive money from the same source the following year.69 This could impact eligibility whether a guaranteed income is implemented through a new program, a “dividend”, or as part of an expanded state EITC – as HUD regulations do not explicitly exempt state tax refunds or credits.

However, there may be some avenues for flexibility for local public housing authorities (PHAs) – local governmental entities that administer certain housing programs. Federal regulations allow these agencies to adopt permissive deductions in the public housing program for certain cash payments from a household’s income. Such deductions have been successful in excluding payments from smaller guaranteed income demonstrations in San Francisco70 and Providence, Rhode Island,71 but have not been attempted for larger, publicly funded, permanent programs.

For more detail on interactions with Housing Benefits see Appendix D.

FundingState Considerations: Sources of Public Funding

To date, most guaranteed income programs have been funded by private philanthropic dollars. As state-level stakeholders look at opportunities to scale these programs, private donations will not be sufficient to sustain larger programs.

In the short term, there are opportunities to utilize federal dollars from various COVID relief efforts, particularly funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). ARPA provides $350 billion in funding to states, counties, metropolitan cities, municipal governments,72 with the first half of funding being received in May 2021, and the second half to arrive in 2022. Units of government receiving these funds have tremendous discretion to utilize the funds to:

- Support public health expenditures;

- Address negative economic impacts caused by the public health emergency;

- Replace lost public sector revenue;

- Provide premium pay for essential workers; and

- Invest in water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure.

In its interim final rule guidance the Treasury Department states that:

a cash transfer program may focus on unemployed workers or low- and moderate-income families, which have faced disproportionate economic harms due to the pandemic. Cash transfers must be reasonably proportional to the negative economic impact they are intended to address. Cash transfers grossly in excess of the amount needed to address the negative economic impact identified by the recipient would not be considered to be a response to the COVID-19 public health emergency or its negative impacts.73

In its final rule, effective April 1, 2022, Treasury maintains the interim final rule guidance and clarifies that it may be presumed that “low- and moderate-income households (as defined in the final rule), as well as households that experienced unemployment, food insecurity, or housing insecurity, experienced a negative economic impact due to the pandemic.”74

While this guidance is somewhat limiting, it does provide an opening for states to fund cash transfers to residents most impacted by the pandemic, and could be supplemented with other state dollars to encompass a broader population. States should think about how best to maximize these dollars so that they get to people most in need.75 For more information on potential sources of public funds, consult this Economic Security Project Fact Sheet.

In the long term, in order for a state program to be permanent it must be funded by tax dollars, and those who have more should pay more. Guaranteed income envisions not only a program that provides a basic standard of living for people struggling most, but a program that is redistributive – funded by taxation of people and entities who have the most income and wealth (and the least need) – and distributed to people with the least income and wealth and most need, thus shrinking inequality through equitable revenue raising and redistribution. In order to fund a guaranteed income for its no-income, low-income and middle-income residents, states should examine the full breadth of their revenue raising powers and increase tax burdens on the richest individuals and corporations, and could consider taxing wealth, income, or both. The federal government utilizes a graduated tax rate where income within higher brackets is taxed at a greater percentage than income in lower brackets – generally equating toward those with higher income paying more money in taxes. However, some states have regressive flat income taxes, or no income tax at all, and could consider funding a guaranteed income through implementation of a graduated tax system to more equitably tax the income of high earners in the state.76 For other states, instituting a state wealth tax – perhaps through the form of an estate or inheritance tax – could be a viable strategy for public funding.77

Wage earners or not, every person deserves to be able to meet their basic needs, and through these programs states can make a profound statement of compassion for their lowest-income individuals regardless of employment status and ensure that those who are working finally begin to reap greater rewards from the massive wealth they are creating.

Racial EquityA Guaranteed Income Can Promote Racial Equity

In the United States, racism is the default mode. Enslavement of Black people and the genocide of Indigenous people remain unaddressed original sins critical to the country’s founding, expansion, economic growth, and accumulation of wealth by white people. What followed were decades of discriminatory policies that stifled the ability of Black people and other people of color to benefit from their labor, housing discrimination through redlining and racial steering, and targeted exclusion of Black families from government aid all fueled by the proliferation of racist narratives and stereotypes that continue to infect the social safety net. Any public policy seeking to combat racial inequity must do so affirmatively and explicitly, and a guaranteed income is no different. A guaranteed income has the potential to contribute to racial equity by being truly accessible to Black families in contrast to many current public benefits tarnished by racist history, anti-Blackness, and outright exclusion of Black families that continues to impact access,

- seeking to challenge narratives about who is deserving of assistance,

- contemplating designs that account for the material economic circumstances created by racism by providing higher payments to Black and Indigenous people, and

- including robust immigrant eligibility.

A guaranteed income alone will not solve racial inequity, but it can play a necessary role in disentangling engrained societal notions about what people deserve, and who is deserving.

Racism in Current Benefits Structures

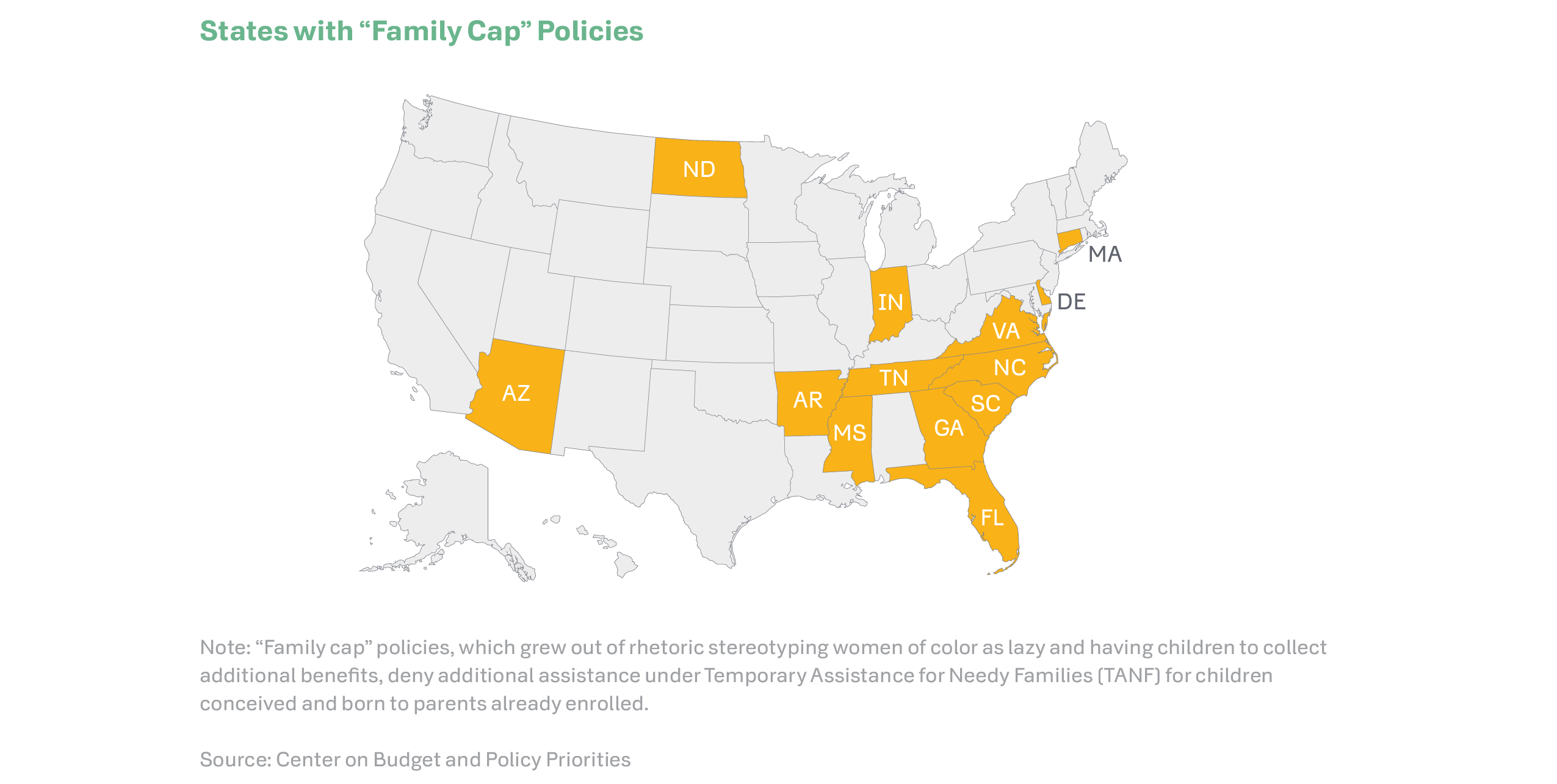

A guaranteed income provides an opportunity for states to address the seemingly facially neutral policies of federal public benefits programs that have historically excluded communities of color. In refusing to replicate these policies in a guaranteed income program, states can help its residents in these communities meet the needs of themselves and their families. Public benefits programs continue to enact racist practices that embrace and perpetuate white supremacist features, such as:

“Family Caps”

130k

children in CA denied benefits in a year because of “family caps.”

XX%

Please provide a brief description for this statistic.

Benefits are often calculated based on family size. Since the 1990s some states have implemented policies that deny or reduce benefits to families who have additional children while receiving benefits. These policies were justified by false and racist narratives depicting Black mothers as irresponsible and having additional children simply to increase their welfare allotments.78 According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a total of 22 states instituted these policies, with 13 states continuing to enforce “family caps” as of 2020. While some states like California have repealed their “family cap,” an estimated 130,000 children were denied benefits because of the “family cap” while it was in effect.79

Drug Testing

A 2019 report by the Center on Law and Social Policy found that 13 states maintain drug screening policies in their TANF cash assistance programs. These policies require applicants to answer a questionnaire supposedly designed to screen for the possibility of substance abuse, and then applicants are drug tested if the screening reveals “a reasonable suspicion.”80 Just like the broader “War on Drugs” these policies are fueled by false racist stereotypes.81

Consideration of Prior Justice Involvement

Over-policing in communities of color and a deeply racist criminal legal system have led to disproportionate rates of incarceration for Black, Latino/a/x, and Indigenous communities.82 According to a 2021 report by the Sentencing Project, when compared to white people, the rate of incarceration is 5 times higher for Black people and 1.3 times higher for Latino/a/x people. While incarceration data for Indigenous communities are subject to a number of limitations,83 in 2010 the incarceration rate of Native Americans was 38 percent higher than the national rate.84 Given these disproportionalities, exclusion based on prior justice involvement in benefits eligibility is another racist feature of the current benefits structure. The “War on Drugs” and its racialized impact, for example, casts a particularly long shadow on public benefits programs. It led to bans on applicants with drug felony convictions in SNAP and TANF, which 25 states still maintain, at least partially, in the TANF program.85 Additionally, 20 states still account for prior felony drug convictions in their SNAP programs – sometimes requiring that applicants show proof of completed probation or drug counseling – with South Carolina continuing to maintain an outright ban.86 Similarly, public housing authorities have the discretion to deny housing on the basis of prior drug-related

criminal activity.87

Asset Limits Disproportionately Favoring White People

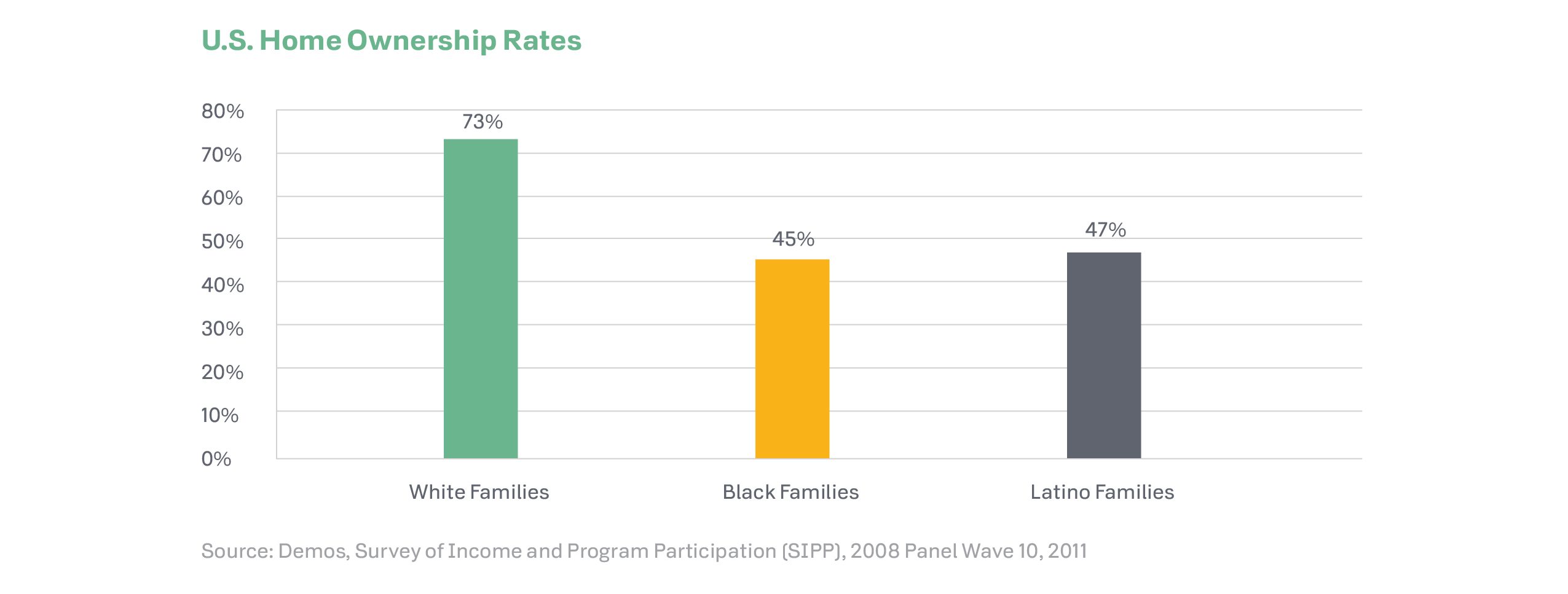

Some public benefits programs deploy asset tests to determine need and eligibility. However, one consistent feature of asset tests is an exclusion of one’s home as a considered asset,88 greatly favoring white people who are more likely to own their home. Indeed, one of the biggest factors in this racial wealth gap is the disparity in homeownership. In 2011, 73 percent of white households owned their own homes, while only 47 percent of Latino/a/x households and 45 percent of Black households were homeowners.89 From the continuing impact of Black people’s exclusion from the GI Bill, redlining, and the retreat from desegregation in public education, as well as the targeting of communities of color for subprime mortgages, racist public policy has shaped these disparities, leaving them impossible to overcome without race-conscious policy change.90

Work Requirements

Work requirement policies represent one of the most insidious forms of racism and anti-Blackness in public benefits structures because of their direct lineage to racist narratives dating back to slavery. During slavery, white slaveowners created the trope of Black people as lazy to justify their participation in a cruel system of bondage and forced labor of enslaved Black people.91 Post-abolition, these tropes led to the proliferation of other forms of coerced labor for Black people.92 These racist stereotypes were also present in the denial of benefits to Black people in the Mother’s Pension program of the late 19th century and the Aid for Dependent Children (ADC) program (the predecessor to Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and eventually TANF). Many southern states, where Black populations remained concentrated, implemented policies denying benefits to “able-bodied” people who were not working during the harvesting season and enforced these policies primarily against Black people in an attempt to force them – including children as young as seven – into the fields to work.93 These policies set the stage for later decades where a federal work requirement would be implemented in the AFDC program and carried through into the TANF and Food Stamp program (predecessor to SNAP) as part of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, commonly known as “welfare reform,” in 1996.

Despite white people making up the largest share of public benefits recipients in the United States, there has been careful and intentional effort to bolster racist historical narratives that associate “public benefits” and “welfare” with Black people – particularly Black women, so that racial and gender bias can be weaponized to degrade the social safety net. Nowhere is this more evident than Ronald Reagan’s conjuring of the mythical “welfare queen.”94 Ronald Reagan built upon historical stereotypes of Black people as “lazy” by using the image of a Black woman to deride what he falsely described as rampant fraud and “free-riding.” This imagery proved extremely potent. The research of political scientist Martin Gilens shows just how prolific these racist beliefs had become by the 1990s. Analyzing survey data, Gilens found that the majority of white Americans believed that Black people could be “just as well off as whites if they only tried harder.” Gilens concluded, “were it not for Whites’ negative views of Blacks’ commitment to the work ethic, support for the least-favored welfare programs might more closely resemble the nearly unanimous support that education, health care, and programs for the elderly currently enjoy.”95

These attitudes were apparent when then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton’s pledge to “end welfare as we know it”96 was met with tremendous enthusiasm. Clinton kept his promise by signing the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which eviscerated federal cash assistance, transforming it from an entitlement to a block grant and adding harsher work requirements and time-limits while doubling down on existing racist policies like “family caps” and “drug-testing.”

Advocates for a guaranteed income must name the cruel history and racist features of the current public benefits infrastructure.

Embracing program names that include words like “supplemental” and “temporary,” makes clear that many aspects of the social safety net are not truly intended to meet people’s basic needs. Racism has been a key contributor to this philosophy. A guaranteed income has the opportunity to put forth a different vision.

To promote racial equity, advocates for a guaranteed income must name the cruel history and racist features of the current public benefits infrastructure and reject the racialized framing of recipients as “deserving” or “undeserving.” Critically a guaranteed income also rejects underlying assumptions around the relationship between public benefits and traditional work and untethers a person’s value from their ability to earn wages. Instead a guaranteed income uplifts the notion that every person is entitled to have their basic needs met and live with dignity. Together we have the resources to provide for each other; it is not only possible and beneficial, but immoral to do otherwise.

Considering Race-Targeted Benefits in Pursuit of Equity

True racial equity will require that generations of racialized harms be met with a sustained commitment to race-conscious solutions. Guaranteed income programs not only provide a platform for a long overdue narrative shift around public benefits recipients, but they could also provide a mechanism to materially reduce racial income disparities by providing higher payments to Black and Indigenous people. In some ways, the racial justice contributions of smaller scale privately-funded guaranteed income demonstrations are easier to conceptualize because some have been explicitly targeted based on race or within historically disadvantaged neighborhoods. However, there has been some examination of how permanent, publicly funded cash transfers programs could be designed to achieve economic justice and racial equity. For example, Dorian Warren’s Universal PLUS model of basic income which “calls for an additional payment to be dispersed to Black families on top of the standard benefits given to all families over a period of time.” As described in a report by the Roosevelt Institute, “The ‘plus model’ acknowledges that the wealth created in the US is inextricably linked to Black labor, sweat, and tears, and this community has never received the benefits created from that labor.” This type of “targeted universalism” recognizes and seeks to redress the negative accumulation resulting from generations of racial inequities in income, wealth, and opportunity.97

Unlike the Universal PLUS model – which would pay some income to everyone and engage in race targeting to provide more income over time to Black families, a guaranteed income would not achieve the same goal of much needed reparations, repairing a history of slavery and race-based exclusion. A guaranteed income program prioritizes channeling money to low-income, no-income, and middle-income people; while there could be additional payments based on the race of eligible individuals, higher income Black and Indigenous people who are entitled to reparations, would not receive a guaranteed income. Racial justice demands that some form of material economic justice be achieved, and there is room for states to think creatively about how a guaranteed income could play a role.

Opportunities for Immigrant Eligibility

Guaranteed income programs and other state-based cash transfers represent the greatest opportunity to create economic justice for immigrant communities that have long been excluded from federal programs. Throughout history, racist rhetoric and policymaking98 has led to the exclusion of undocumented immigrants from federal programs such as SNAP, TANF (and its predecessor AFDC), Medicaid, SSI, and others, with only limited availability to other immigrant groups who are “lawfully present” in the United States.99 In 1996, federal welfare reform created two categories of immigrants for benefits eligibility purposes: “qualified” and “not qualified.” Some groups of immigrants who are “qualified” for federal programs include legal permanent residents (LPRs or green card holders), asylees, refugees, people fleeing abuse, or survivors of trafficking. However, even these categories of immigrants can face additional restrictions or “wait periods”, such as the 5-year federal ban on benefits for qualified immigrant groups who must be present in the U.S. for five years or work.100 For “not qualified” immigrants, such as the 10.5 to 12 million101 undocumented immigrants in the country, federal programs are largely unobtainable.

This structural inequity, coupled with decades of cruel immigration policies, has made it harder for immigrants to obtain economic stability. States have an opportunity to provide needed support and progress toward economic and racial justice for immigrant communities excluded from the social safety net by ensuring robust immigrant eligibility for state-funded cash transfer programs. Some states provided benefits both before and during the pandemic, to try to address some of the shortfall of federal programs and federal relief passed in response to COVID-19. California established a $125 million fund to help undocumented workers who cannot access unemployment insurance. Oregon added $20 million to the Oregon Worker Relief Fund which was created to provide temporary financial relief to undocumented workers. Connecticut provided a total of $3.5 million to aid undocumented families with rent relief and direct financial aid. Lastly, in Fiscal Year 2021 Illinois began providing Medicaid coverage for low-income seniors regardless of immigration status, making it the first state to cover older undocumented immigrants.102 Nothing in federal law would prevent states from providing state funds to immigrants in the form of a guaranteed income or other cash transfers, and offering long-overdue support to immigrants who are critical to the success of our communities.103

ConclusionConclusion

The legacy of so-called “welfare reform” and decades of disinvestment have resulted in a social safety net that perpetuates racism and is fundamentally incapable of allowing people to meet their basic needs and live with dignity. It is time to boldly reimagine the social safety net, eliminate deep poverty and provide stability to middle income households by implementing a guaranteed income. Ultimately, a federal program should be vigorously pursued, but a mass movement needs to be built to overcome gridlock at the federal level. States have a vital role to play as leaders in building public policy. Through creation of state-level guaranteed income programs funded through equitably raised revenue, states can progress toward economic justice for their lowest-income residents regardless of employment status, supplement the existing safety net, and build necessary momentum toward a federal program needed to meet current and coming economic challenges.

Appendix A: State Considerations: Building Wealth

A guaranteed income is a direct and effective strategy to ensure that everyone can meet their basic needs and reduce unconscionable levels of income inequality. However, even wider disparities exist when it comes to wealth. Available data shows that guaranteed income allows people to save money, pursue additional education and training, and improve their employment situation, all of which can increase a household’s opportunity to invest and accumulate wealth, but states should strongly consider wealth building strategies that are more direct to complement a guaranteed income.

One such model is baby bonds. The basic idea of a baby bond is that children in eligible families would have an initial deposit placed into a government managed trust that would guarantee growth of the investment until the child turns 18. Upon their 18th birthday, the child is able to access the money – which will have appreciated significantly – and, in most models, is limited to using it for specific purposes such as pursuing higher education, buying a home, or starting a business.104 However, states could adopt and modify such a policy, remove restrictions on how the money is eventually spent, and pair this asset building strategy with cash transfers like guaranteed income to produce even greater outcomes.105 In 2021, Connecticut became the first state in the country to pass a statewide baby bond program106 while state legislators in other states, like New Jersey, Iowa, and Maryland, have also introduced proposals.107

Local governments have been invested in baby bonds programs as well. Since 2017, the City of Oakland has funded Oakland Promises’ Brilliant Baby program – a College Savings Account program – for Oakland families under 200% FPL, where $500 is placed in a qualifying child’s 529 account108 and can be accessed when they turn 18 and used toward college tuition.109 The District of Columbia has also recently created a municipal level baby bonds program for eligible D.C. families under 300% FPL where, similar to other proposals, an initial deposit of $1,000 followed by annual deposits based on income will be placed into an invested trust fund that children can access when they turn 18 to pay for education, buying a home, or other qualified expenses.110 Most baby bonds models consider a household’s income when assessing eligibility. Just as a guaranteed income is targeted to households based on their level of income, wealth building policies may be more appropriately targeted based on a household’s wealth (assets and resources) rather than income. As discussed above, cash transfer policies like guaranteed income could be extremely potent in mitigating disparities in income, but matching cash payments with policies that build assets in a targeted manner could better address the massive disparity in intergenerational wealth transfers – especially for people of color – which is a critical piece in promoting both racial and economic equity.111

Appendix B: SNAP: Implications of a Publicly Funded Guaranteed Income

Unless explicitly excluded, federal SNAP regulations include “payments from Government-sponsored programs, dividends, interest, royalties, and all other direct money payments from any source which can be construed to be a gain or benefit,” as unearned income that is counted during the eligibility determination.112 For privately-funded guaranteed income demonstrations, there are some SNAP provisions that have been used to exclude certain lump sum and recurring payments from consideration in SNAP.113 However, for publicly funded state programs, the analysis is more complex and depends on the state’s choices regarding implementation strategy and frequency of payment.

If states choose to implement a guaranteed income through expansion of a state EITC, federal law provides a strong case for exclusion of these payments from the income eligibility determination in SNAP, especially if paid as a lump sum. With respect to the federal EITC, 26 U.S. Code § 6409 provides “[n]otwithstanding any other provision of law, any refund (or advance payment with respect to a refundable credit) made to any individual under this title shall not be taken into account as income, and shall not be taken into account as resources for a period of 12 months from receipt, for purposes of determining the eligibility of such individual (or any other individual) for benefits or assistance (or the amount or extent of benefits or assistance) under any Federal program or under any State or local program financed in whole or in part with Federal funds.” The federal EITC is a refundable tax credit covered by this provision, and as such it is not counted as income in federal public benefits programs and is only counted as an asset after 12 months. However, state and local earned income tax credits that are paid in a lump sum are also exempted as income under 7 CFR 273.9(c)(8), which states that “money received in the form of a nonrecurring lump-sum payment, including, but not limited to, income tax refunds, rebates, or credits, is not counted as income.” Further, state and local earned income tax credits are explicitly excluded as a resource for purposes of the SNAP asset test in 7 CFR 273.8(e)(12). Accordingly, implementing a guaranteed income by expanding a state or local earned income tax credit would not jeopardize SNAP eligibility if paid out in a lump sum.

However, the income exclusion for state and local tax refunds seems to be predicated on the credits being non-recurring, so models that seek to deviate from lump sum in favor of periodic payments may put SNAP eligibility at risk.

For states choosing to implement a guaranteed income through dividend payments from a sovereign wealth fund, Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend provides the best example for how such payments could affect SNAP eligibility. Alaska counts the Permanent Fund Dividend as both unearned income for the month it was received, and a resource/ asset. The state of Alaska does not use broad-based categorical eligibility, and as such, its SNAP recipients are subject to the asset test laid out in federal law.114 However, it is unclear whether the payment’s consideration as unearned income flows from it being a payment from a “government-sponsored program”, its characterization as a “dividend” (which are expressly counted as unearned income under federal law), or both. Many types of non-recurring lump sum payments can be excluded as income for SNAP, but federal law does not define “non-recurring.” 7 CFR 273.9(c)(8). However, the express exemption of income tax refunds and other credits seems to suggest that even payments made on a predictable cycle once a year could still constitute “non-recurring.” Additionally, a lump sum “dividend” payment will likely count as a resource for SNAP recipients who are subject to an asset test, but for states that use SNAP broad-based categorical eligibility (BBCE)115 to increase or waive asset limits, this may not pose a concern. To mitigate the impact of the PFD on SNAP eligibility, Alaska set up a Hold Harmless Fund to pay benefits to families who lose eligibility because of dividend payments, and receives waivers116 from the federal government allowing them to temporarily suspend SNAP cases for up to four months until eligibility is regained, so the state does not have to terminate the SNAP case and force recipients to re-apply.

For states seeking to establish a new program with public funds, recurring payments will likely jeopardize SNAP eligibility. Some privately-funded demonstrations have been able to exclude payments from being included in SNAP income determinations, but the same provisions that relay this flexibility cannot be used for publicly funded programs. When the source of the payments is private, federal statute and corresponding regulations allow states to elect to exclude from consideration in SNAP certain payments that are excluded in TANF – where states maintain much more flexibility in defining income eligibility.117 States choosing to exclude payments under this provision “must specify in its [SNAP] State plan of operation that it has selected this option and provide a description of the resources that are being excluded.”118 State plans of operation are then subject to approval by USDA. However, both federal law and regulation explicitly forbid states from using this provision to exclude “regular payments from a government source,” with 7 CFR 273.9(c)(19) further specifying that payments or allowances a household receives from an intermediary that are funded from a government source are also considered payments from a government source, thus opening the door for recurring payments from private sources, but not government, or public sources. Accordingly, changes in federal law may be required to permit exclusion of recurring guaranteed income payments that are funded with public dollars. However, as discussed above, the interaction with lump sum payments made annually as part of a new program may depend on USDA’s interpretation of“non-recurring.”

Appendix C: Medicaid: Implications of a Publicy Funded Guaranteed Income

MAGI Medicaid

Except for some specific populations, Medicaid generally uses MAGI (Modified Adjusted Gross Income) as defined by the IRS to determine eligibility. For many privately-funded guaranteed income demonstrations, Medicaid eligibility is not affected by receipt of guaranteed income payments because of the IRS definition of “gifts” as non-taxable income.119 Importantly, the IRS does not count as income “governmental

benefit payments from a public welfare fund based upon need.”120 As such, a publicly funded guaranteed income paid as part of a new program or as a “dividend”121 from a sovereign wealth fund that is targeted to individuals based on income would likely be exempt. It’s worth noting that payments made universally likely would not be exempt and may require waivers or special permission from the federal government to exempt from consideration in MAGI Medicaid. For example, Alaska’s PFD is considered taxable for federal income tax purposes and needs to be reported to the IRS.122 However, Alaska’s PFD is subject to a special income disregard for all Medicaid categories, and thus does not affect income eligibility for Medicaid recipients in the state.123

For states seeking to implement a guaranteed income via an expansion of a state EITC, there may be some complications with MAGI Medicaid eligibility. While a federal tax refund and refundable tax credits like the federal EITC are clearly excluded from consideration as income in federal programs,124 state tax refunds, as well as state credits and offsets, are included by the IRS as taxable income if the tax filer claimed an itemized deduction for state taxes that were later refunded. While the majority of tax filers do not itemize deductions, with even fewer itemizing after the increase in the standard deduction as part of the Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, states should proceed with caution in program design, and advise guaranteed income recipients about the potential impacts of tax choices to ensure that MAGI Medicaid program eligibility will not be affected. While some benefits such as SNAP could be replaced by a Hold Harmless Fund, there is no suitable cash replacement for health insurance coverage.

Non-MAGI Medicaid

There are some categories of Medicaid recipients who are non-MAGI, such as those who are over 65, blind, or have a disability. For these groups, Medicaid eligibility is generally determined using the income methodologies of the SSI program administered by the Social Security Administration.125 While Non-MAGI cases have posed challenges for privately funded demonstrations,126 assistance based on need which is wholly funded by a State or one of its political subdivisions, does not count as unearned income and would not be considered in determining eligibility for non-MAGI Medicaid. For purposes of this rule, assistance is “based on need” when it is provided under a program which uses the amount of a person’s income as one factor to determine your eligibility. As such, a guaranteed income implemented as part of a new program, or as a payment from a sovereign wealth fund in the form of a “dividend” would likely not affect non-MAGI Medicaid eligibility so long as the payments are targeted to individuals based on income level. 20 CFR 416.1124(c)(2).

As with MAGI Medicaid, implementing a guaranteed income through expansion of a state EITC could threaten eligibility for non-MAGI Medicaid. While federal tax refunds and refundable credits are excluded from consideration, the same is not true for state tax refunds and credits. For example, state tax refunds are counted as a resource in the month they are received when determining income eligibility for SSI unless another income exclusion applies.127 However, for purposes of non-MAGI Medicaid, it appears states have

some discretion with how to treat state tax credits and refunds in the income eligibility determination.

For example, in Illinois, state tax refunds are counted as an asset for non-MAGI eligibility, but the portion of the state tax return that is from an earned income credit is not to be included as either an asset or asincome.128 In order to protect eligibility for non-MAGI Medicaid, states should use any available flexibility to exempt state EITCs from consideration, should they choose that strategy for implementation of a guaranteed income.

Appendix D: Housing Benefits: Implications of a Publicly Funded Guaranteed Income